In baseball, a “full count” refers to a specific situation during an at-bat when the count to the batter consists of two strikes and three balls. This means that the batter has had two strikes called against them and three balls thrown outside the strike zone.

In this scenario, one more ball will result in the batter being awarded a walk, allowing them to advance to first base. Conversely, a strike will result in an out, assuming the batter doesn’t hit a fair ball. A full count is often considered a crucial and tense moment in a baseball game, both for the batter and the pitcher.

Full Count Terminology

The origin of the term “full count” could be traced back to older scoreboards that utilized empty spaces instead of numerals to indicate the accumulation of three balls and two strikes, representing the maximum count achievable during a live plate appearance.

To this day, numerous scoreboards continue to employ light bulbs to convey this information, resulting in a situation where a 3-2 count is represented by all the bulbs being brightly illuminated.

In softball, the term “full house” is often used as an alternative, which is likely influenced by the poker hand called a “full house.” In poker, a full house comprises three cards of the same value and a pair, and this terminology has found its way into the realm of softball.

Payoff Pitch

A “payoff pitch” is a commonly used term to describe a pitch thrown when the count is full. This pitch is highly advantageous for the batter to swing at, as it presents a favorable opportunity.

When the umpire has already called three balls, the pitcher must exercise utmost precision to avoid missing the strike zone. Failing to do so would result in ball four, granting the batter a walk.

In situations where there are two outs in an inning, baserunners who are susceptible to being put out through a force play typically choose to run on any 3-2 pitch, regardless of their speed.

This strategy is employed because various outcomes can occur, such as the batter walking (forcing runners to advance), the batter striking out to end the inning, the batter fouling off the pitch (allowing runners to return to their original bases), or the batter putting the ball into play.

What Happens On A Full Count?

In a full-count situation between a pitcher and batter, numerous possibilities can unfold, contingent upon the specific game scenario. Here is a brief overview of what one can anticipate:

Catchers

Catchers are not bound by any regulations that prohibit communication with hitters. Within the realm of baseball strategy, this practice is referred to as “working the hitter.”

During a full count situation, hitters devote their complete attention to anticipating the forthcoming pitch. In order to disrupt their concentration, astute catchers employ the tactic of engaging in conversation.

Anecdotal tales suggest that Gary Carter, a revered Hall of Fame catcher, showcased remarkable prowess in working hitters.

As the story goes, he even managed to induce the renowned Tony Gwynn into striking out by consistently disclosing the upcoming pitch (which, incidentally, most hitters find displeasing).

Pitchers

Once three balls have been thrown, pitchers are well aware that a single additional pitch outside the strike zone will result in a runner reaching base. Consequently, pitchers opt to deliver a pitch that falls within the boundaries of the strike zone.

By doing so, they provide hitters with an improved opportunity to connect with the ball since they recognize that the pitcher must execute a strike.

Baserunners

When baserunners are present, they undergo training to initiate their run toward the next base immediately after the pitcher releases the ball.

This strategic approach aims to provide the runners with a head start in the event that the ball is put into play.

Furthermore, it presents a challenge for the defensive team to execute a double play, particularly when there are fewer than two outs. In cases where there are two outs, the probability of the runners being forced out also diminishes.

Do Full Counts Favor Batters or Pitchers?

When the count reaches 3-2, the crucial “payoff pitch” determines the outcome of the encounter in favor of either the pitcher or the batter on the next delivery, regardless of the result (unless the pitch is fouled off).

So, when this decisive moment arrives, who has the advantage?

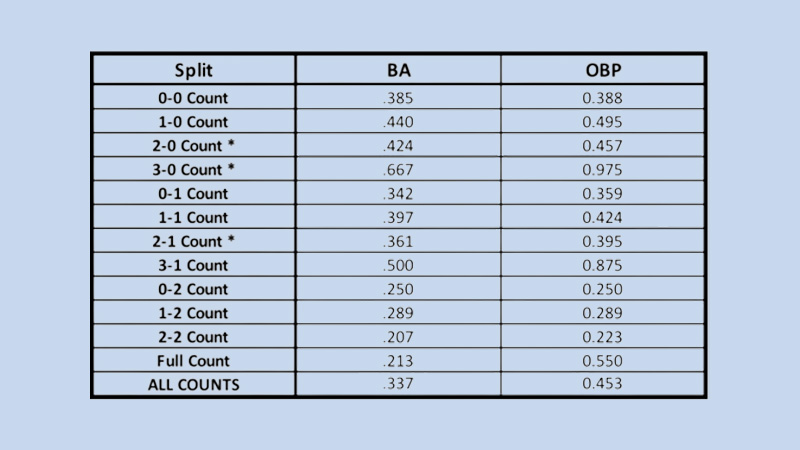

In 2019, Major League Baseball as a whole struggled to hit with a mere .202 batting average in full-count situations, but they managed an impressive on-base percentage of .453.

Out of the 26,676 full counts recorded that year, 31.2% resulted in a walk, 27.7% ended with a strikeout, 13.8% concluded with a hit, and the remaining resulted in in-play outs.

Without considering the walks, batters faced difficulties hitting in full counts, although not to the same extent as other two-strike counts (0-2, 1-2, 2-2), where they had batting averages of .149, .161, and .180, respectively.

Similarly, their walk rates were significantly lower compared to those in 3-0 and 3-1 counts.

The fact that the on-base percentage of .453 in 3-2 counts is the closest to a 50-50 split among all counts highlights the lack of room for error for both sides.

How Common Are Full Counts in Baseball?

Full counts occur due to a combination of factors involving the pitcher’s ability to work off the plate and the batter’s patience and discipline, allowing the count to progress without ending prematurely.

Nevertheless, full counts are fairly frequent. During the 2019 MLB season, there were 26,676 plate appearances that reached a full count, averaging just under 11 per game.

This count ranked as the third most common conclusion to plate appearances that season, trailing only 1-2 and 2-2 counts.

This accounted for approximately 14.3% of the total 186,517 plate appearances throughout the season. With contemporary baseball strategies placing greater importance on working the count, the number of full counts has notably increased in recent years.

Historical Data of Full Count Stats

In the year 2010, the count of full counts in plate appearances ranked third in terms of frequency. However, there were only 23,553 instances of full counts observed, averaging 9.7 per game.

Interestingly, this occurred despite a slightly lower number of plate appearances throughout the league for the entire season, with a difference of less than a thousand.

Delving deeper into the statistics, in 2010, a noteworthy 12.7% of all plate appearances concluded with a full count, slightly surpassing the figure of 12.6% recorded in 2000.

If we look back to 1991, the landscape was quite different. Back then, only 8.6 full counts occurred per game, making it the fourth most common outcome in a plate appearance.

A mere 11.6% of plate appearances reached a full count during that period. By examining the data on the most prevalent ending counts, we can gain insights into the evolving offensive strategies, particularly regarding pitch selection.

Conversely, during the years 1991 and 2000, the prevailing tendency was for plate appearances to be resolved on the first pitch. However, in both 2010 and 2020, the first-pitch outcome ranked as the fourth most common occurrence.

The decline in plate appearances ending on the first pitch and the rise in full counts are undoubtedly not mere coincidences. This trend shows no signs of abating, indicating a likelihood of witnessing an even greater frequency of full counts in the future.

Why Do Baserunners Run on Full Counts?

If you’ve had the opportunity to watch a substantial amount of baseball, chances are you’ve come across a scenario where a hitter finds themselves in a full count, prompting the baserunners to take off as soon as the pitch is thrown.

Similar to any other instance when a runner is initiated, there is a specific rationale behind this strategy. However, in this particular situation, the reasoning is relatively straightforward.

The majority of managers choose to start runners on a full count and fewer than two outs due to the high likelihood of a walk, which in turn reduces the possibility of a double play if the ball is put in play.

When there are two outs, any runner in a force situation will invariably run on a full count because they cannot be caught stealing under these circumstances.

To delve deeper into the matter, when two outs are recorded, and a runner is in a force situation (meaning there is a runner on first, second, or third base, and each subsequent base is occupied), there are minimal consequences to initiating the runner early.

This is because, with two outs, if the batter swings and misses, the inning concludes anyway, and if a walk or hit occurs, the runner would advance to the next base regardless.

Benefit

The primary advantage of initiating runners on a full count lies in the event of a hit. By starting the runners in this situation, there is an increased likelihood of a baserunner advancing an extra base on a hit.

For instance, it could enable a slower runner to score from first base on a double when they might not have been able to do so otherwise.

In scenarios with less than two outs, managers may opt to start runners in force situations, primarily with the aim of avoiding a double play.

Risks

Nevertheless, there are substantial risks associated with sending runners in these circumstances.

Firstly, if a batter makes contact with the ball, but it is caught by the defense, the chances of a runner being doubled off are significantly higher since they are farther away from their previous base.

Notably, there have been instances where at least three unassisted triple plays have occurred as a direct result of starting two runners on a 3-2 count with no outs.

These situations highlight the potential pitfalls and risks involved in initiating runners on full counts.

The Bottom Line

Furthermore, another common outcome is the occurrence of a “strike-’em-out, throw-’em-out” double play. In this scenario, the batter strikes out, and a runner is subsequently thrown out while attempting to steal the next base.

During the 2019 season, there were 123 instances where runners were caught stealing on 3-2 counts, ranking it as the second-highest count for such occurrences that year.

When there are fewer than two outs, the decision to send the runner(s) is often influenced by factors such as the speed of the runner and the hitting ability of the batter at the plate.

However, when there are two outs, these factors become irrelevant, and the decision is not dependent on them.

Nevertheless, regardless of the specific circumstances, when the count reaches a full count, there is always an air of drama and tension as the battle intensifies with the slimmest margin for error.

It becomes a compelling quest to determine who will emerge victorious in this high-stakes situation.